JBRA Assisted Reproduction 2013; 17 (2):101-108

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20130015

Serum AMH level can predict the risk of cycle cancellation and the chances of good ovarian response, independently of patient’s age or FSH

AMH sérico pode predizer o risco de cancelamento de ciclo e as chances de boa resposta ovariana, independentemente da idade ou FSH

1Centro de Investigaciones Endocrinológicas, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CEDIE-CONICET), División de Endocrinología, Hospital de Niños R. Gutiérrez, C1425EFD Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2Centro Médico Seremas, C1124AAD Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Accredited Redlara center

4Instituto de Biología y Medicina Experimental, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (IBYME-CONICET), C1428ADN Buenos Aires, Argentina.

ABSTRACT

Objective: In the recent years, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) has been shown to represent a reliable marker of the ovarian reserve. In this study, we evaluate the risk of cycle cancellation and the chances of good ovarian response to controlled hyperstimulation and of pregnancy according to serum AMH measured prior to assisted reproduction procedures in females undergoing intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

Method: An analytic observational study included females undergoing ICSI between in a single center. Subgroup analyses were performed by grouping patients according to FSH levels or to their age.

Results: The risk of cycle cancellation decreased from 64% in patients with serum AMH ≤3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL) to 21% with AMH ≥15 pmol/L (2.10 ng/mL). The rate of good response increased from almost null in patients with AMH ≤3 pmol/L to 61% in those with AMH ≥15 pmol/L. Pregnancy rate increased moderately, but significantly, from 31% with AMH ≤3 pmol/L to 35% with AMH ≥15 pmol/L.

Conclusion: Here we provide estimates of those outcomes according to the values of serum AMH, in general and in subgroups according to patient’s age or serum FSH, which are helpful for the clinician and the couple in their decision making about starting an ART treatment.

Keywords: Anti-Müllerian hormone; metaphase II oocytes; ICSI outcome; cycle cancellation, ovarian reserve.

RESUMO

Objetivo: Nos últimos anos, o hormonio anti-mülleriano (AMH) tem sido demonstrado como um marcador confiável da reserva ovariana. Neste estudo, avaliamos o risco de cancelamento do ciclo e as chances de boa resposta ovariana à hiperestimulação controlada e de gravidez, de acordo com o HAM no soro, medido antes de procedimentos de reprodução assistida em mulheres submetidas à injeção intracitoplasmática de espermatozóides.

Método: Um estudo analítico observacional incluiu mulheres submetidas a ICSI em um único centro. As análises dos subgrupos foram realizadas em pacientes agrupadas de acordo com os níveis de FSH ou para a sua idade.

Resultados: O risco de cancelamento do ciclo diminuiu de 64% em doentes com níveis séricos de HAM ≤% 3 pmol / L (0,42 ng / mL) a 21% com HAM ≥ 15 pmol / L (2,10 ng / mL). A taxa deboa resposta aumentou de quase nula em pacientes com HAM ≤ 3 pmol / L a 61% naqueles com AMH ≥ 15 pmol / L. A taxa de gravidez aumentou moderada, mas significativamente, de 31%, com HAM ≤ 3 pmol / L até 35% com HAM ≥ 15 pmol / L.

Conclusão: Aqui fornecemos estimativas desses resultados de acordo com os valores de HAM no soro, em geral e em subgrupos de acordo com a idade do paciente ou de FSH, que são úteis para o clínico e para o casal em sua tomada de decisão sobre como iniciar um tratamento de RA.

Palavras-chave: hormonio anti-mulleriano; oócitos metáfase II; ICSI; cancelamento de ciclos; reserva ovariana.

INTRODUCTION

The human ovary contains a limited population of primordial follicles, set approximately 20 weeks post-conception, when the ovary follicle reserve achieves its maximum size. Thereafter, the ovarian reserve decreases, having an impact on natural fertility which clearly declines after the age of 30 (te Velde and Pearson2002, Nelson et al. 2011). The age of women giving birth is increasing worldwide due to diverse social reasons. Consequently, a growing number of couples is facing age-related infertility problems and seek medical assistance. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) outcomes have improved over the years but are limited by the ovarian response to hyperstimulation used in treatment protocols. On the other hand, ART treatments are expensive for healthcare systems or private practices and represent a stressful situation for the couple. Therefore, the necessity exists for optimization of the evaluation of the ovarian reserve in order to minimize the uncertainty of the outcome of ART procedures. Age and circulating FSH levels, which have classically been used to predict the fertility potential, lack precision under specific clinical circumstances, especially because there is a considerable variability regarding the ovarian reserve amongst women of the same age (Broekmans et al. 2007).

The ovarian reserve is determined by the number of primordial follicles present in the ovary and their quality. Reliable markers of oocyte quality are yet to be developed, and direct assessment of the pool of primordial follicles present in the ovaries is not feasible. However, the number of antral follicles represents a good estimator of the primordial follicle pool and, therefore, of the quantitative aspect of the ovarian reserve (Hendriks et al. 2007, Broer et al. 2009). In the recent years, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) has been shown to represent a reliable marker of the ovarian reserve (Broekmans et al. 2006) and of the response to ovarian stimulation (Feyereisen et al. 2006, La Marca et al. 2010, Broer et al. 2011, Anderson et al. 2012). A member of the TGFβ superfamily initially believed to be a fetal testis hormone (Josso et al. 2006), AMH is also produced in the ovary essentially by the granulosa cells of primary and small antral follicles (Rey et al. 2000). Serum AMH levels are clearly correlated with the granulosa cells mass, ranging from undetectable in normal post-menopause (Rey et al. 1996) and in Turner syndrome patients with absence of gonadal tissue (Hagen et al. 2010) to very high levels in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (Fallat et al. 1997, Pigny et al. 2006) or granulosa cell tumors (Long et al. 2000). A particular advantage of AMH as a marker of ovarian reserve is its insignificant variation during the menstrual cycle (Cook et al. 2000, La Marca et al. 2006, Hehenkamp et al. 2006), which does not restrict AMH measurement to a particular stage of the cycle. The first in-house AMH immunoassays developed in 1990 (Josso et al. 1990, Hudson et al. 1990, Baker et al. 1990) were replaced by commercial assays after 1998 (Rey et al. 1999, Long et al. 2000, Cook et al. 2002). The two different commercially available AMH assays used in the following 10 years showed clear differences in the reported levels, mainly in the low female range (Fréour et al. 2007), which complicates the interpretation of the results for the clinician. Furthermore, the large number of studies assessing the performance of serum AMH as a predictor of the ovarian reserve and a prognostic factor for the outcome of ART treatments have mostly used only one cutoff value, as summarized in a recent meta-analysis (Broer et al. 2009), thus dividing the population into two groups: one below the cutoff value usually of homogeneously poor prognosis, and another one above the cutoff value which is extremely heterogeneous. Furthermore, although the effect of age and of other reproductive variables on serum AMH has been acknowledged for years, most of the studies have analyzed serum AMH in the studied samples as a whole, or after introducing complex correction factors in the statistical analysis which hamper a simple interpretation of the AMH value observed in an individual patient presenting to the clinician.

The adequate identification of the responsiveness potential specific for the serum AMH level in each patient before entering an ART treatment may be most helpful for the couple in order to decide whether to start treatment and for the clinician in the proper management regarding the stimulation protocol. The objective of this work was to provide the clinician with a reliable tool to predict the most commonly used reproductive outcomes in women undergoing intracytoplasmatic sperm injection (ICSI) before starting the procedure. To fulfill this objective we assessed the clinical value of different serum levels AMH in predicting the rates of: cycle cancellation, good response to ovarian stimulation, syngamy, cleavage, implantation and clinical pregnancy. The assessment was performed separately according to patients’ age (25-37 and 38-43 yr) and to serum FSH (normal or elevated).

METHODS

Study subjects and design

Subjects

We performed an observational study, retrospectively collecting data from 145 consecutive women, aged 25 to 43 years-old, undergoing ICSI at Seremas Institute (Buenos Aires, Argentina) between August 2009 and October 2010. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Ovarian stimulation

All patients were submitted to a standard GnRH agonist protocol, and underwent controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with recombinant FSH (Gonal-F; Serono Laboratories, Switzerland). Ovulation was induced with highly purified hCG (Ovidrel, Serono). Daily FSH doses and timing of hCG administration were adjusted according to the usual criteria of follicle maturation (Fanchin et al. 2003). Follicle count was performed by ultrasonography using a transvaginal probe.

Serum hormone levels

Serum was obtained at first visit for AMH measurement, and during ovarian stimulation on day 3 (d3) for FSH and E2 measurement and on the day of hCG administration (d-hCG) for E2 measurement. AMH was measured at the Centro de Investigaciones Endocrinológicas, Hospital Ricardo Gutiérrez (Buenos Aires, Argentina), using an ultrasensitive enzyme-linked immunoassay specific for human AMH (EIA AMH/MIS®, Immunotech, Beckman-Coulter Co., Marseilles, France, ref. A11893), recently validated by our group (Grinspon et al. 2012). FSH and estradiol (E2) were measured by chemiluminescense using Access® technology (Beckman Coulter Inc.).

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)

Conventional ICSI, as previously described (Brugo Olmedo et al. 2000), was conducted ~5 hours post oocyte aspiration. Motile sperm were isolated using the swim up technique. Around 2 μl of sperm were placed in 7% polyvinylpyrrolidone and a sperm was injected into each oocyte using standardized techniques. The embryos were cultured in a single droplet containing 20 μl of medium and incubated at 37°C under controlled conditions (5% CO2, 5% O2 and 90% N2). All embryo transfers were performed 72 hours after oocyte aspiration.

Outcome measures

The main outcome measure was the absolute risk (risk rate) of cycle cancellation (number of patients with cancelled cycles divided by the total number of patients in whom a cycle was initiated), good response to ovarian stimulation (defined as ≥ 5 oocytes retrieved at the time of aspiration), syngamy, cleavage at 48 h, multinucleated embryos, implantation (defined as the number of gestational sacs observed on ultrasound) and clinical pregnancy (defined as the presence of fetal heart activity detected by ultrasound at 6 weeks) for each of the following serum AMH levels: 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 pmol/L. Secondary outcome measures were the predictive values of: patient’s age, serum FSH and estradiol on d3, and serum estradiol and follicle count by ultrasound assessment on d-hCG.

Statistical analyses

Data distribution was assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data of the risk rates of cycle cancellation, good response to ovarian stimulation, syngamy, cleavage at 48 h, multinucleated embryos, implantation and clinical pregnancy are presented with their 95% confidence intervals. Patient’s age, basal serum AMH, FSH and estradiol, and serum estradiol and follicle count by ultrasound assessment on the day of ovulation induction by hCG administration are presented as the median and interquartile range. Comparisons between 2 groups were made using an unpaired t test, except when a non-Gaussian distribution was found, where a Mann-Whitney test was used. Areas under the ROC curves were calculated for age and hormone levels to estimate the predictive values for the rates of: cycle cancellation, good response to ovarian stimulation, syngamy, cleavage at 48 h, multinucleated embryos, implantation and clinical pregnancy. Analyses wer performed for the whole group, and independently according to age, where the study cohort was divided into 2 groups (25-37 yr and 38-43 yr), or according to FSH levels, where the study cohort was divided into 2 groups (FSH within the normal reference range and FSH above the reference range). The absolute risk values were compared using a one-sided Fisher’s exact test. The level of significance was set at P <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 5.01 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS

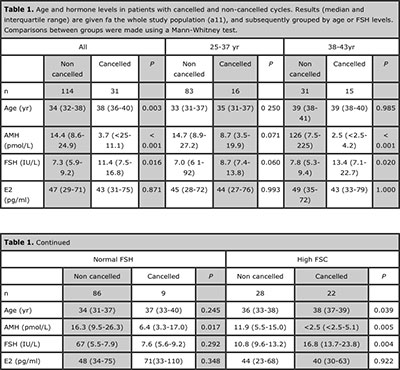

Cycle cancellation

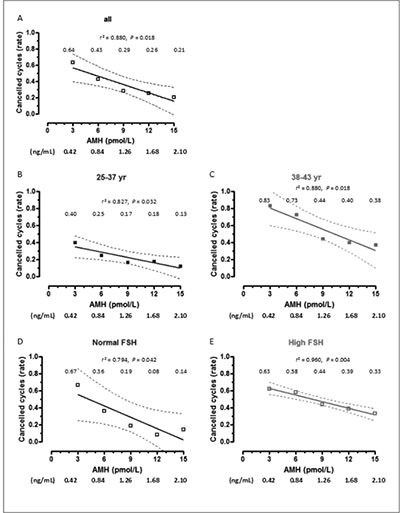

In the whole group analyzed, age and FSH-d3 were significantly higher, and AMH was lower in patients with cancelled cycles, as expected. No difference was observed in E2-d3 (Table 1). When patients were grouped by age, the significantly lower AMH and higher FSH values were still observed in patients aged 38-43 yr with cancelled cycles. When patients were classified according to their FSH levels, lower AMH levels were observed in patients with cancelled cycles irrespective of their FSH levels. Serum AMH showed excellent areas under the ROC curves to predict cycle cancellation in the whole group and in the age and FSH subgroups (Table 2). The absolute risk of cycle cancellation was inversely correlated to serum AMH in the whole group (Figure 1, A) and in the subgroups (Figure 1, B-E). The risk of cycle cancellation in the whole group decreased from 64% in patients with serum AMH ≤ 3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL) to 43% in patients with AMH 6 pmol/L (0.84 ng/mL), 29% with AMH 9 pmol/L (1.26 ng/mL), 26% with AMH 12 pmol/L (1.68 ng/mL) and 21% with AMH ≥15 pmol/L (2.10 ng/mL). When related to patients with AMH < 3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL), the relative risk of cycle cancellation was 0.42 in patients with AMH between 6-9 pmol/L (0.84-1.26 ng/mL) and 0.37 in patients with AMH >15 pmol/L (>2.1 ng/mL) (Table 3). Interestingly, cycle cancellation occurred in approximately 2/3 of the patients with AMH ≤ 3 pmol/L irrespective of the FSH level (Figure 1, D and E). However, with higher AMH values the risk of cycle cancellation decreased more significantly in patients with normal FSH.

Oocyte retrieval

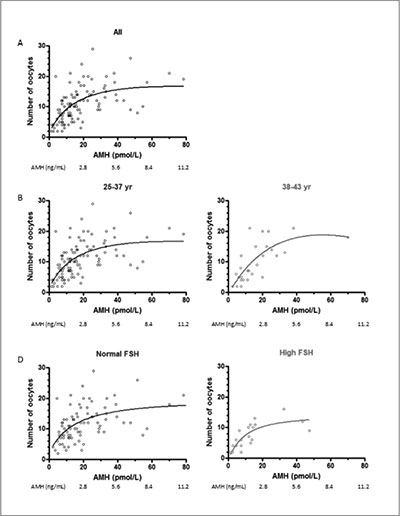

The number of oocytes retrieved in non-cancelled cycles increased progressively in correlation with serum AMH up to an AMH level of 40 pmol/L (5.6 ng/mL) and plateaued thereafter (Figure 2). The increase was observed irrespective of age or serum FSH, yet with a lower absolute number of oocytes in patients aged 38-43 years or with elevated FSH.

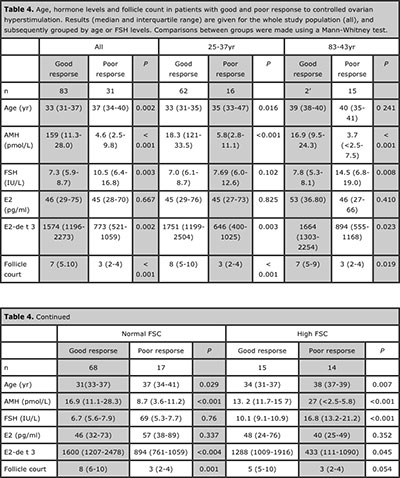

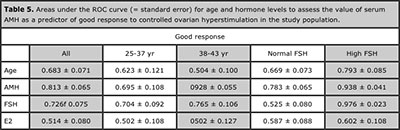

Serum AMH showed the most significant differences between patients with good and poor response to stimulation, i.e. retrieval of 5 or more oocytes (Table 4). Among basal serum hormone determinations, AMH also showed areas under the ROC curves of high performance to predict a good response (Table 5).

The rate of good response increased with serum AMH: it was almost null in patients with AMH ≤ 3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL) in both age groups (Figure 3) and rose up to 61% in those patients with AMH 15 pmol/L (2.10 ng/mL). When related to patients with AMH < 3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL), the chances of good response were approximately eight-fold higher in patients with AMH between 6-12 pmol/L (0.84-1.68 ng/mL) and eleven-fold higher in patients with AMH >15 pmol/L (>2.1 ng/mL) (Suppl. Table). The positive correlation between good response and AMH was also significant, but with lower absolute rates, when patients were grouped according to their age (Figure 3, B-C) or FSH levels (Figure 3, D-E).

Figure 1. Absolute risk (risk rate) of cancelled cycles as a function of AMH levels. Patients were grouped according to age or FSH levels. Rates are shown for serum AMH at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 pmol/L (equivalences for AMH in ng/mL are given below the X axis of each graph). Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 2. Number of oocytes retrieved at the time of aspiration as a function of AMH levels (non-linear regression). Patients were grouped according to age or FSH levels.

Figure 3. Absolute risk (risk rate) of good response to ovarian stimulation, defined as ≥ 5 oocytes retrieved at the time of aspiration, as a function of AMH levels. Patients were grouped according to age or FSH levels. Rates are shown for serum AMH at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 pmol/L (equivalences for AMH in ng/mL are given at the bottom of the figure). Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 4. Absolute risk (risk rate) of clinical pregnancy rates as a function of AMH levels. Patients were grouped according to age or FSH levels. Rates are shown for serum AMH at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15 pmol/L (equivalences for AMH in ng/mL are given at the bottom of the figure). Dotted lines represent the 95% confidence interval.

Table 1. Age and hormone levels in patients with cancelled and non-cancelled cycles. Results (median and interquartile range) are given fa the whole study population (a11), and subsequently grouped by age or FSH levels. Comparisons between groups were made using a Mann-Whitney test.

Table 2. Areas under the ROC curve (= standard error) for age and hormone levels to assess the value of serum AMH as a predictor of cycle cancellation in the study population.

Table 3. Relative risk (RR) of cycle cancelation and good response (RR was considered as 1 in patients with AMH < 3 pmol/L).

Table 4. Age, hormone levels and follicle count in patients with good and poor response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Results (median and interquartile range) are given for the whole study population (all), and subsequently grouped by age or FSH levels. Comparisons between groups were made using a Mann-Whitney test.

Table 5. Areas under the ROC curve (= standard error) for age and hormone levels to assess the value of serum AMH as a predictor of good response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in the study population.

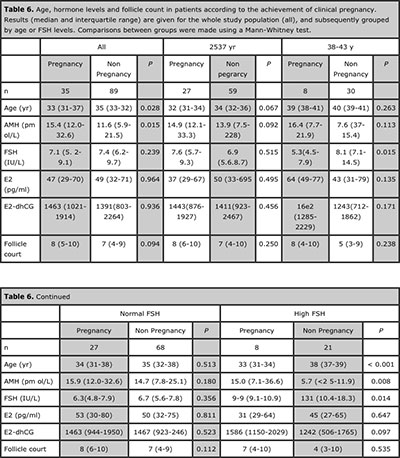

Table 6. Age, hormone levels and follicle count in patients according to the achievement of clinical pregnancy. Results (median and interquartile range) are given for the whole study population (all), and subsequently grouped by age or FSH levels. Comparisons between groups were made using a Mann-Whitney test.

Syngamy, cleavage, implantation and pregnancy rates

No significant correlation was found between AMH levels and the rates of syngamy (Spearman r -0.080, P=0.313), cleavage at 48 h (Spearman r -0.004, P=0.623), multinucleated embryos (Spearman r -0.062, P=0.457) or implantation (Spearman r -0.053, P=0.557).

The rate of pregnancy showed an increase in correlation with serum AMH in the whole group. Serum AMH was lower and age was higher in patients with a higher pregnancy rate when the analysis was performed in the whole group (Table 6). Interestingly, this was also observed in patients with high FSH. A significantly positive correlation between pregnancy rate and AMH was observed in the whole group (Spearman r 0.894, P=0.020, Figure 4 A), and in patients <38 yr (Figure 4 C) or with high FSH (Figure 4 E).

DISCUSSION

One of the most critical aspects before starting an ART procedure is the initial evaluation of the female’s capacity to produce healthy and developmental competent oocytes. Serum AMH has become a standard determination to evaluate the ovarian reserve. In the present study, we report the results of the rates of cancelled cycles, good response to stimulation and pregnancy according to the level of circulating AMH in a random sample obtained prior to initiating the ART procedure. Many authors have analyzed the prognostic performance of serum AMH in women undergoing ART treatments and have provided strong evidence about the validity of AMH as a predictor of reproductive outcomes (Broer et al. 2010) and references therein). Most of these studies provide correlation coefficients or sensitivity and specificity levels for a given AMH cutoff, using adequate statistical procedures to avoid confounders. The strength of the association is thus unequivocally proven, yet the application of the results in clinical practice is not straightforward. In the present work we have used a practical approach and provide useful and easily applicable results of serum AMH levels to predict the risk of cycle cancellation and the chances of good response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and pregnancy in females undergoing an ART procedure, according to their age or FSH level.

Our results are in line with those previously reported by other authors showing that AMH is a useful marker for predicting cycle cancellation (Friden et al. 2011) and poor response to ovarian stimulation (Broer et al. 2009), representing a better predictor than the other classically associated parameters such as FSH, estradiol and age (Jayaprakasan et al. 2010). Interestingly, our data show the special importance of serum AMH in women aged >38 yr or with high serum FSH, and have immediate application for the clinician and the patient in their decision prior to start hormonal stimulation. For example, in women 38-43 yr seeking for assisted reproduction treatment, an AMH value ≥ 15 pmol/L (2.10 ng/mL) indicates a risk of 38% to result in a cycle cancellation, and the risk increases to 83% if AMH is ≤ 3 pmol/L (0.42 ng/mL). Also, different AMH values are helpful for decision making in both patients with normal or elevated FSH levels.

It is well established that AMH is correlated with the number of oocytes retrieved at the time of aspiration (Seifer et al. 2002). Our results are consistent with this observation, independently of the patient’s age. Furthermore, from a practical standpoint, we show that AMH is particularly useful to predict ovarian response to stimulation, as shown by the best areas under the ROC curves. Only E2-dhCG showed a better area under the ROC curve; yet, it cannot be used as a predictor before starting the stimulation protocol.

In our hands, AMH was not as powerful as a predictor of oocyte quality in terms of fertilization rate, embryo development and implantation. Although we found a correlation between serum AMH and pregnancy rate in the whole group, the effect magnitude was modest, in line with the controversial results reported by other groups showing no (Hazout et al. 2004, Silberstein et al. 2006, Lekamge et al. 2007) or moderate usefulness of AMH in predicting embryo development (La Marca et al. 2010, Lie Fong et al. 2008). However, it was interesting to note that AMH was more discriminant in the high-risk groups, i.e. in the patients >38 yr or with high FSH.

In conclusion, in an individual patient seeking for assisted reproductive technology treatment, the serum AMH level measured in a previous cycle can be used to predict the risk of cycle cancellation and the chances of good ovarian response, when analyzed together with patient’s age or serum FSH. Serum AMH has a significantly better predictive value than FSH and follicle count particularly in women > 38 yr. Furthermore, serum AMH is useful to predict reproductive outcomes in patients with a mild to moderate increase in FSH levels. Although our study design does not allow us to conclude that an infertility treatment should be interrupted on the basis of low AMH, our results add to the existing evidence, and provide practical information, on the usefulness of serum AMH level to help clinicians and patients estimate the chances of good treatment outcomes before initiating the stimulation protocol. AMH evaluation is not routinely performed prior to stimulation and should be incorporated into the initial screening of the patient.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

R.A. Rey and M.G. Buffone have received research grants from CONICET (Argentina). P. Bedecarrás and R.A. Rey have received honoraria from CONICET (Argentina) for technology services using the AMH ELISA.

REFERENCES

Anderson RA, Nelson SM, Wallace WH (2012) Measuring anti-Mullerian hormone for the assessment of ovarian reserve: when and for whom is it indicated? Maturitas 71:28-33

Medline Crossref

Baker ML, Metcalfe SA, Hutson JM (1990) Serum levels of mullerian inhibiting substance in boys from birth to 18 years, as determined by enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:11-15

Medline Crossref

Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, te Velde ER, Macklon NS, Fauser BC (2007) Female reproductive ageing: current knowledge and future trends. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18:58-65

Medline Crossref

Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, Mol BW, Lambalk CB (2006) A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update 12:685-718

Medline Crossref

Broer SL, Mol BW, Hendriks D, Broekmans FJM (2009) The role of antimullerian hormone in prediction of outcome after IVF: comparison with the antral follicle count. Fertil Steril 91:705-714

Medline Crossref

Broer SL, Mol B, Dolleman M, Fauser BC, Broekmans FJ (2010) The role of anti-Mullerian hormone assessment in assisted reproductive technology outcome. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 22:193-201

Medline Crossref

Broer SL, Dolleman M, Opmeer BC, Fauser BC, Mol BW, Broekmans FJ (2011) AMH and AFC as predictors of excessive response in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: a meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 17:46-54

Medline Crossref

Brugo Olmedo S, Rawe VY, Nodar FN, Galaverna GD, Acosta AA, Chemes HE (2000) Pregnancies established through intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) using spermatozoa with dysplasia of fibrous sheath. Asian J Androl 2:125-130

Medline

Cook CL, Siow Y, Taylor S, Fallat ME (2000) Serum Müllerian inhibiting substance levels during normal mestrual cycles. Fertil Steril 73:859-861

Medline Crossref

Cook CL, Siow Y, Brenner AG, Fallat ME (2002) Relationship between serum müllerian-inhibiting substance and other reproductive hormones in untreated women with polycystic ovary syndrome and normal women. Fertil Steril 77:141-146

Medline Crossref

Fanchin R, Schonauer LM, Righini C, Frydman N, Frydman R, Taieb J (2003) Serum anti-Mullerian hormone dynamics during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Hum Reprod 18:328-332

Medline Crossref

Fallat ME, Siow Y, Marra M, Cook C, Carrillo A (1997) Müllerian-inhibiting substance in follicular fluid and serum: a comparison of patients with tubal factor infertility, polycystic ovary syndrome, and endometriosis. Fertil Steril 67:962-965

Medline Crossref

Fréour T, Mirallié S, Bach-Ngohou K, Denis M, Barrière P, Masson D (2007) Measurement of serum Anti-Mullerian Hormone by Beckman Coulter ELISA and DSL ELISA: Comparison and relevance in Assisted Reproduction Technology (ART). Clin Chim Acta 375:162-164

Medline Crossref

Feyereisen E, Mendez Lozano DH, Taieb J, Hesters L, Frydman R, Fanchin R (2006) Anti-Mullerian hormone: clinical insights into a promising biomarker of ovarian follicular status. Reprod Biomed Online 12:695-703

Medline Crossref

Friden B, Sjoblom P, Menezes J (2011) Using anti-Mullerian hormone to identify a good prognosis group in women of advanced reproductive age. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 51:411-415

Medline Crossref

Grinspon RP, Ropelato MG, Bedecarrás P, Loreti N, Ballerini MG, Gottlieb S, Campo SM, Rey RA (2012) Gonadotrophin secretion pattern in anorchid boys from birth to pubertal age: pathophysiological aspects and diagnostic usefulness. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 76:698-705

Medline Crossref

Hagen CP, Aksglæde L, Sorensen K, Main KM, Boas M, Cleemann L, Holm K, Gravholt CH, Andersson AM, Pedersen AT, Petersen JH, Linneberg A, Kjaergaard S, Juul A (2010) Serum levels of anti-Mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian function in 926 healthy females from birth to adulthood and in 172 Turner syndrome patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5003-5010

Medline Crossref

Hazout A, Bouchard P, Seifer DB, Aussage P, Junca AM, Cohen-Bacrie P (2004) Serum antimullerian hormone/mullerian-inhibiting substance appears to be a more discriminatory marker of assisted reproductive technology outcome than follicle-stimulating hormone, inhibin B, or estradiol. Fertil Steril 82:1323-1329

Medline Crossref

Hehenkamp WJK, Looman CWN, Themmen APN, de Jong FH, te Velde ER, Broekmans FJM (2006) Anti-Mullerian Hormone Levels in the Spontaneous Menstrual Cycle Do Not Show Substantial Fluctuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4057-4063

Medline Crossref

Hendriks DJ, Kwee J, Mol BW, te Velde ER, Broekmans FJ (2007) Ultrasonography as a tool for the prediction of outcome in IVF patients: a comparative meta-analysis of ovarian volume and antral follicle count. Fertil Steril 87:764-775

Medline Crossref

Hudson PL, Dougas I, Donahoe PK, Cate RL, Epstein J, Pepinsky RB, MacLaughlin DT (1990) An immunoassay to detect human mullerian inhibiting substance in males and females during normal development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:16-22

Medline Crossref

Jayaprakasan K, Campbell B, Hopkisson J, Johnson I, Raine-Fenning N (2010) A prospective, comparative analysis of anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin-B, and three-dimensional ultrasound determinants of ovarian reserve in the prediction of poor response to controlled ovarian stimulation. Fertil Steril 93:855-864

Medline Crossref

Josso N, Legeai L, Forest MG, Chaussain JL, Brauner R (1990) An enzyme linked immunoassay for anti-Müllerian hormone: a new tool for the evaluation of testicular function in infants and children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:23-27

Medline Crossref

Josso N, Picard JY, Rey R, Clemente N (2006) Testicular Anti-Müllerian Hormone: History, Genetics, Regulation and Clinical Applications. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 3:347-358

Medline

La Marca A, Stabile G, Artenisio AC, Volpe A (2006) Serum anti-Mullerian hormone throughout the human menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod 21:3103-3107

Medline Crossref

La Marca A, Sighinolfi G, Radi D, Argento C, Baraldi E, Artenisio AC, Stabile G, Volpe A (2010) Anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) as a predictive marker in assisted

Medline Crossref

Lekamge DN, Barry M, Kolo M, Lane M, Gilchrist RB, Tremellen KP (2007) Anti-Mullerian hormone as a predictor of IVF outcome. Reprod Biomed Online 14:602-610

Medline

Lie Fong S, Baart EB, Martini E, Schipper I, Visser JA, Themmen AP, de Jong FH, Fauser BJ, Laven JS (2008) Anti-Mullerian hormone: a marker for oocyte quantity, oocyte quality and embryo quality? Reprod Biomed Online 16:664-670

Medline

Long WQ, Ranchin V, Pautier P, Belville C, Denizot P, Cailla H, Lhommé C, Picard JY, Bidart JM, Rey R (2000) Detection of minimal levels of serum anti-Müllerian hormone during follow-up of patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumor by means of a highly sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:540-544

Medline Crossref

Rey RA, Lhommé C, Marcillac I, Lahlou N, Duvillard P, Josso N, Bidart JM (1996) Antimüllerian hormone as a serum marker of granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: comparative study with serum alpha-inhibin and estradiol. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:958-965

Medline Crossref

Rey R, Sabourin JC, Venara M, Long WQ, Jaubert F, Zeller WP, Duvillard P, Chemes H, Bidart JM (2000) Anti-Müllerian hormone is a specific marker of Sertoli- and granulosa-cell origin in gonadal tumors. Hum Pathol 31:1202-1208

Medline Crossref

Nelson SM, Messow MC, McConnachie A, Wallace H, Kelsey T, Fleming R, Anderson RA, Leader B (2011) External validation of nomogram for the decline in serum anti-Mullerian hormone in women: a population study of 15,834 infertility patients. Reprod Biomed Online 23:204-206

Medline Crossref

Pigny P, Jonard S, Robert Y, Dewailly D (2006) Serum Anti-Mullerian Hormone as a Surrogate for Antral Follicle Count for Definition of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:941-945

Medline Crossref

Rey RA, Belville C, Nihoul-Fékété C, Michel-Calemard L, Forest MG, Lahlou N, Jaubert F, Mowszowicz I, David M, Saka N, Bouvattier C, Bertrand AM, Lecointre C, Soskin S, Cabrol S, Crosnier H, Léger J, Lortat-Jacob S, Nicolino M, Rabl W, Toledo SP, Bas F, Gompel A, Czernichow P, Josso N (1999) Evaluation of gonadal function in 107 intersex patients by means of serum antimüllerian hormone measurement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:627-631

Medline Crossref

Seifer DB, MacLaughlin DT, Christian BP, Feng B, Shelden RM (2002) Early follicular serum müllerian-inhibiting substance levels are associated with ovarian response during assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril 77:468-471

Medline Crossref

Sillberstein T, MacLaughlin DT, Shai I, Trimarchi JR, Lambert-Messerlian G, Seifer DB, Keefe DL, Blazar AS (2006) Mullerian inhibiting substance levels at the time of HCG administration in IVF cycles predict both ovarian reserve and embryo morphology. Hum Reprod 21:159-163

Medline Crossref

te Velde ER Pearson PL (2002) The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update 8:141-154

Medline Crossref